“被发明的亚历山大大帝的历史”教会历史有多假?(完·附评论)

“被发明的亚历山大大帝的历史”教会历史有多假?(完·附评论)

How Fake Is Church History?

译文简介

根据教科书上的年表,帕台农神庙建于2500年前。它现在的状态似乎与那个遥远年代相符,但很少有人知道它在1687年被威尼斯迫击炮击中的炸弹炸毁时仍然完好无损。

正文翻译

According to our textbook chronology, the Parthenon was built 2,500 years ago. Its current state may seem consistent with such old age, but few people know that it was still intact in 1687, when it was blown up by a bomb shot by a Venetian mortar. The French painter Jacques Carrey had made some fifty-five drawings of it in 1674, which served later for its restoration.

根据教科书上的年表,帕台农神庙建于2500年前。它现在的状态似乎与那个遥远年代相符,但很少有人知道它在1687年被威尼斯迫击炮击中的炸弹炸毁时仍然完好无损。法国画家雅克·凯瑞(Jacques Carrey)在1674年为它画了大约55幅画,这些画后来用于修复。

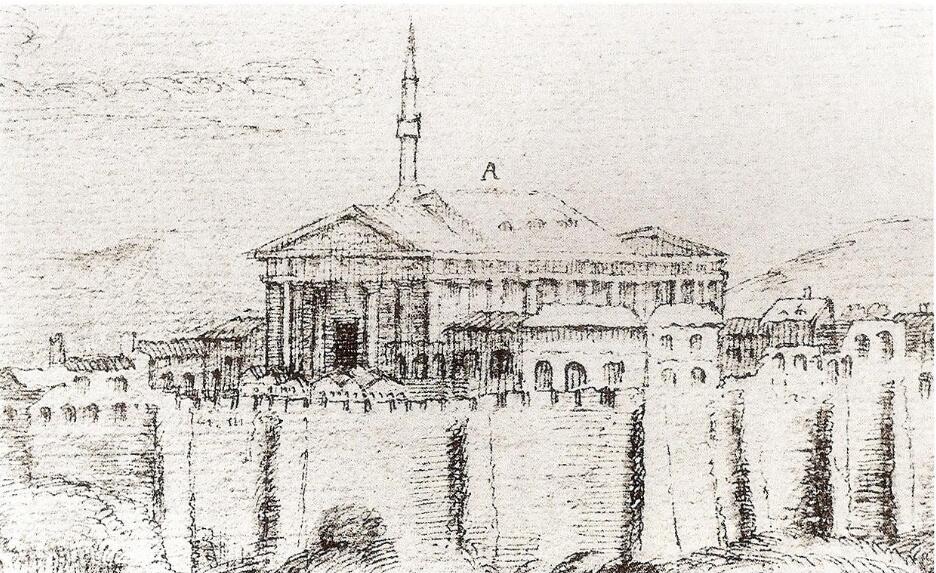

In ancient times, we are told, the Parthenon housed a gigantic statue of Athena Parthenos (“Virgin”), while in the sixth century it became a church dedicated to “Our Lady or Athens,” until it was turned into a mosque by the Ottomans. Strangely enough, historian William Miller tells us in his History of Frankish Greece that the Parthenon is not mentioned in medi texts before around 1380, when the King of Aragon describes it as “the most precious jewel that exists in the world.” The Acropolis was then known as “the Castle of Athens.” Could it be a medi fortified city from the start? Is Ancient Greece a fantasy? Or is it simply wrongly dated?

我们被告知,在古代,帕台农神庙里有一座巨大的雅典娜·帕台农斯(“处女”)雕像,而在六世纪,它成为一座献给“我们的圣母或雅典”的教堂,直到被奥斯曼人变成清真寺。奇怪的是,历史学家威廉·米勒在他的《法兰克希腊史》中告诉我们,在1380年左右,中世纪文献中没有提到帕台农神庙,当时阿拉贡国王将其描述为“世界上最珍贵的宝石”。

雅典卫城当时被称为“雅典城堡”。难道它从一开始就是一座中世纪的设防城市吗?古希腊是一个幻想吗?或者,只是日期搞错了?

我们被告知,在古代,帕台农神庙里有一座巨大的雅典娜·帕台农斯(“处女”)雕像,而在六世纪,它成为一座献给“我们的圣母或雅典”的教堂,直到被奥斯曼人变成清真寺。奇怪的是,历史学家威廉·米勒在他的《法兰克希腊史》中告诉我们,在1380年左右,中世纪文献中没有提到帕台农神庙,当时阿拉贡国王将其描述为“世界上最珍贵的宝石”。

雅典卫城当时被称为“雅典城堡”。难道它从一开始就是一座中世纪的设防城市吗?古希腊是一个幻想吗?或者,只是日期搞错了?

In the frxwork of our hypothesis that, between the eleventh and the fifteenth century, Rome invented or embellished its own Republican and Imperial Antiquity as propaganda to cheat Constantinople of its birthright, it makes sense that Rome would also invent or embellish a pre-byzantine Greek civilization as a way of explaining its own Greek heritage without acknowledging its debt to Constantinople. To explain how Greek culture had filled the world before reaching Rome, Alexander the Great and his Hellenistic legacy were also invented.

在我们假设的框架下,在11世纪到15世纪之间,罗马发明或美化了自己的共和国和帝国古代,作为宣传,抹黑扭曲君士坦丁堡的与生俱来的权利,罗马也发明或美化了前拜占庭希腊文明,作为解释自己的希腊遗产的一种方式,而不承认它对君士坦丁堡的债务。为了解释希腊文化在到达罗马之前是如何遍布世界的,亚历山大大帝和他的希腊文化遗产也被发明了出来。

Alexander is a legendary figure. According to his most sober biography, due to Plutarch, at the age of 22, this Macedonian prince (educated by Aristotle) set out to conquer the world with about 30,000 men, founded seventy cities, and died at the age of 32, leaving a fully formed Greek-speaking civilization that stretched from Egypt to Persia. Sylvain Tristan remarks, after Anatoly Fomenko, that the Seleucids (Seleukidós), who ruled Asia Minor after Alexander, bear almost the same name as the Seljukids (Seljoukides) who controlled that same region from 1037 to 1194. Is the Hellenistic civilization another phantom image of the Byzantine commonwealth, pushed back in the distant past in order to conceal Italy’s debt to Constantinople?

亚历山大是一个传奇人物。根据普鲁塔克所写的他最严肃的传记,这位马其顿王子(受亚里士多德教育)在22岁时带领大约3万人开始征服世界,建立了70座城市,并在32岁时去世,留下了一个从埃及延伸到波斯的完整的希腊语文明。西尔万·特里斯坦在安东尼·福缅科(译注:被考证为历史发明家)之后评论说,在亚历山大之后统治小亚细亚的西流基王朝与从1037年到1194年控制同一地区的Seljukids (Seljoukides)有着几乎相同的名字。

希腊化文明是拜占庭联邦的另一个幻影,被推回到遥远的过去,以掩盖意大利欠君士坦丁堡的债务?这样的假设似乎有些牵强。但一旦我们意识到我们的年表是一个相对较新的结构,它就变得合理了。希腊化文明是否所拜占庭联邦的另一个幻影,被推回到遥远的过去,以掩盖意大利对君士坦丁堡的债务吗?

亚历山大是一个传奇人物。根据普鲁塔克所写的他最严肃的传记,这位马其顿王子(受亚里士多德教育)在22岁时带领大约3万人开始征服世界,建立了70座城市,并在32岁时去世,留下了一个从埃及延伸到波斯的完整的希腊语文明。西尔万·特里斯坦在安东尼·福缅科(译注:被考证为历史发明家)之后评论说,在亚历山大之后统治小亚细亚的西流基王朝与从1037年到1194年控制同一地区的Seljukids (Seljoukides)有着几乎相同的名字。

希腊化文明是拜占庭联邦的另一个幻影,被推回到遥远的过去,以掩盖意大利欠君士坦丁堡的债务?这样的假设似乎有些牵强。但一旦我们意识到我们的年表是一个相对较新的结构,它就变得合理了。希腊化文明是否所拜占庭联邦的另一个幻影,被推回到遥远的过去,以掩盖意大利对君士坦丁堡的债务吗?

Such hypothesis seems farfetched. But it becomes plausible once we realize that our chronology is a relatively recent construction. In the Middle Ages, there existed no accepted long chronology scanning millenniums. If today Wikipedia tells us that Alexander the Great was born on July 21, 356 BC and died on June 11, 323 BC, it is simply because some sixteenth-century scholar declared it so, using arbitrary guesswork and a biblical measuring tape. However, with the recent progress of archeology, the problems met by our received chronology have accumulated into a critical mass.

这样的假设似乎有些牵强。但一旦我们意识到我们的年表是一个相对较新的结构,它就变得合理了。在中世纪,没有公认的囊括千年的长年表。如果今天维基百科告诉我们亚历山大大帝出生于公元前356年7月21日,死于公元前323年6月11日,这只是因为一些16世纪的学者用武断的猜测和圣经的卷尺宣布了这一点。

然而,随着近年来考古学的进步,我们所接受的年代学所遇到的问题已经积累到临界点。

这样的假设似乎有些牵强。但一旦我们意识到我们的年表是一个相对较新的结构,它就变得合理了。在中世纪,没有公认的囊括千年的长年表。如果今天维基百科告诉我们亚历山大大帝出生于公元前356年7月21日,死于公元前323年6月11日,这只是因为一些16世纪的学者用武断的猜测和圣经的卷尺宣布了这一点。

然而,随着近年来考古学的进步,我们所接受的年代学所遇到的问题已经积累到临界点。

Here is one example, mentioned by Sylvain Tristan: the “Antikythera mechanism” is an analogue computer composed of at least 30 meshing bronze gear wheels, used to predict astronomical positions and eclipses for calendar and astrological purposes decades in advance. It was retrieved from the sea in 1901 among wreckage from a shipwreck off the coast of the Greek island Antikythera. It is dated from the second or first century BC. According to Wikipedia, “the knowledge of this technology was lost at some point in Antiquity” and “works with similar complexity did not appear again until the development of mechanical astronomical clocks in Europe in the fourteenth century.” This technological chasm of 1,500 years is perhaps easier to believe when one already believes that the heliocentric model developed by Greek astronomer Aristarchus of Samos in the third century BC was totally forgotten until Nicolaus Copernicus reinvented it in the sixteenth century AD. But skepticism is here less extravagant that the scholarly consensus.

这里有一个例子,西尔万·特里斯坦提到:“Antikythera机制”是一个模拟计算机,由至少30个啮合的青铜齿轮组成,用于提前几十年预测天文位置和日食,用于日历和占星术目的。1901年,在希腊岛Antikythera海岸的一艘船残骸中,它从海上打捞出来。它的日期是公元前2世纪或公元前一世纪。根据维基百科的说法,“在古代的某个时刻,这种技术的知识已经消失了”,“在14世纪的欧洲发展机械天文钟之前,“类似复杂性的作品并没有再次出现。”

公元前3世纪,早已被彻底遗忘的希腊天文学家萨摩斯的阿里斯塔克斯提出了日心说模型,直到公元16世纪尼古拉·哥白尼才重新发明了这个模型的时候,1500年的技术差距可能更容易让人相信。但在这里,怀疑主义没有学术共识那么占主流。

这里有一个例子,西尔万·特里斯坦提到:“Antikythera机制”是一个模拟计算机,由至少30个啮合的青铜齿轮组成,用于提前几十年预测天文位置和日食,用于日历和占星术目的。1901年,在希腊岛Antikythera海岸的一艘船残骸中,它从海上打捞出来。它的日期是公元前2世纪或公元前一世纪。根据维基百科的说法,“在古代的某个时刻,这种技术的知识已经消失了”,“在14世纪的欧洲发展机械天文钟之前,“类似复杂性的作品并没有再次出现。”

公元前3世纪,早已被彻底遗忘的希腊天文学家萨摩斯的阿里斯塔克斯提出了日心说模型,直到公元16世纪尼古拉·哥白尼才重新发明了这个模型的时候,1500年的技术差距可能更容易让人相信。但在这里,怀疑主义没有学术共识那么占主流。

The number of skeptics has grown in recent years, and several researchers have set out to challenge what they call the Scaligerian chronology (standardized by Joseph Scaliger in his book De emendatione temporum, 1583). Most of these “recentists,” whom we will introduce in our next article, focus on the first millennium AD. They believe that it is much too long, in other words, that Antiquity is closer to us than we think. They actually find themselves in agreement with the Renaissance humanists who, according to historian Bernard Guenée, thought of the “middle age” between Antiquity and their time (the term media tempestas first appears in 1469 in the correspondence of Giovanni Andrea Bussi) as “nothing but a parenthesis, an in-between.”

近年来,持怀疑态度的人越来越多,一些研究人员已经开始挑战他们所谓的斯卡利格年表(由约瑟夫·斯卡利格在1583年出版的《时间的修正》一书中标准化)。我们将在下一篇文章中介绍这些“近代主义者”,他们大多关注公元第一个千年。他们认为时间太长了,换句话说,古代比我们想象的更接近我们。事实上,他们发现自己与文艺复兴人文主义者的观点是一致的,根据历史学家Bernard guensame的说法,文艺复兴人文主义者认为古代和他们的时代之间的“中世纪”(media tempestas这个词最早出现在1469年Giovanni Andrea Bussi的通信中)“只不过是一个括号,一个中间”。

近年来,持怀疑态度的人越来越多,一些研究人员已经开始挑战他们所谓的斯卡利格年表(由约瑟夫·斯卡利格在1583年出版的《时间的修正》一书中标准化)。我们将在下一篇文章中介绍这些“近代主义者”,他们大多关注公元第一个千年。他们认为时间太长了,换句话说,古代比我们想象的更接近我们。事实上,他们发现自己与文艺复兴人文主义者的观点是一致的,根据历史学家Bernard guensame的说法,文艺复兴人文主义者认为古代和他们的时代之间的“中世纪”(media tempestas这个词最早出现在1469年Giovanni Andrea Bussi的通信中)“只不过是一个括号,一个中间”。

In 1439, Flavio Biondo, the first archeologist of Rome, wrote a book about this period and titled it: Decades of History from the Deterioration of the Roman Empire. Giorgio Vasari thought of it as a mere two centuries when he wrote in his Life of Giotto (1550), that Giotto (1267-1337) “brought back to life the true art of painting, introducing the drawing from nature of living persons, which had not been practised for two hundred years.”

1439年,罗马第一位考古学家弗拉维奥·比昂多写了一本关于这一时期的书,书名为《罗马帝国衰落的几十年历史》。乔治·瓦萨里在他的《乔托的一生》(1550)中写道,乔托(1267-1337)“将真正的绘画艺术带回了生活,引入了从活生生的人的自然中绘画,这是两百年来没有实践过的。”

1439年,罗马第一位考古学家弗拉维奥·比昂多写了一本关于这一时期的书,书名为《罗马帝国衰落的几十年历史》。乔治·瓦萨里在他的《乔托的一生》(1550)中写道,乔托(1267-1337)“将真正的绘画艺术带回了生活,引入了从活生生的人的自然中绘画,这是两百年来没有实践过的。”

If our Middle Ages have been artificially stretched by seven or more centuries, does that mean that most of it is pure fiction? Not necessarily. Gunnar Heinsohn, using comparative archeology and stratigraphy (explore his articles or watch his video conference), argues that events spread throughout Antiquity, Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages were in fact contemporary. In other words, the Western Roman Empire, the Eastern (Byzantine) Roman Empire, and the Germanic Roman Empire must be resynchronized and seen as parts of the same civilization which collapsed a little more than ten centuries ago, after a global cataclysmic event that caused a commotion of memory and a taste for apocalyptic salvation cults.

如果我们的中世纪被人为地拉长了七个或更多世纪,这是否意味着它的大部分都是虚构的?不一定。贡纳·海因索恩运用比较考古学和地层学(浏览他的文章或观看他的视频会议),认为贯穿古代、古代晚期和中世纪早期的事件实际上是当代的。

换句话说,西罗马帝国,东(拜占庭)罗马帝国和日耳曼罗马帝国必须重新同步,并被视为同一个文明的一部分,这个文明在十多个世纪前崩溃了,在一场全球性的灾难性事件之后,引起了记忆的混乱和对末日救赎崇拜的兴趣。

(完)

如果我们的中世纪被人为地拉长了七个或更多世纪,这是否意味着它的大部分都是虚构的?不一定。贡纳·海因索恩运用比较考古学和地层学(浏览他的文章或观看他的视频会议),认为贯穿古代、古代晚期和中世纪早期的事件实际上是当代的。

换句话说,西罗马帝国,东(拜占庭)罗马帝国和日耳曼罗马帝国必须重新同步,并被视为同一个文明的一部分,这个文明在十多个世纪前崩溃了,在一场全球性的灾难性事件之后,引起了记忆的混乱和对末日救赎崇拜的兴趣。

(完)

评论翻译

很赞 ( 5 )

收藏

I am really enjoying these two articles mainly because they force me to think about what I believe about the history of Western Europe, i.e. Germany, France and England. I am old enough to have been subjected to the “western civilization” curriculum back in the before-times of this kind of revisionism.

First, the fact that these articles are being published anonymously is suspicious. The overall ideological slant of the writing seems to be what you would expect from a former KGB officer in Moscow. The idea seems to be to undermine the legitimacy of the Catholic Church by delving into every imaginable conspiracy and twist of the historical record to confuse people. The KGB produced this kind of Anti-Catholic propaganda for decades. It is fun to read but the whole effect is basically on par with what you get from Alex Jones and the interdimensional lizard aliens theory of who runs international banking.

我真的很喜欢这两篇文章,主要是因为它们迫使我思考我对西欧历史的看法,即德国、法国和英国。在这种修正主义出现之前,我已经足够年长了,可以接受“西方文明”课程的教育。

首先,这些文章是匿名发表的,这一事实令人怀疑。这篇文章的整体意识形态倾向似乎是你对莫斯科前克格勃官员的期望。这个想法似乎是通过深入研究每一个可以想象的阴谋和扭曲的历史记录来混淆人们,从而破坏天主教会的合法性。克格勃几十年来一直在进行这种反天主教的宣传。它读起来很有趣,但整体效果寥寥。

I think it’s a lot more likely that the usual history we learn is closer to the truth, i.e. Alaric sacked Rome and thus began the dark ages on the continent and it took a few hundred years for Europe and the Church to recover from it. Still, even if that’s not true, the question remains “why were the English and Irish converts to Catholicism long before any of these forgeries existed?”

其次,让我承认你所说的关于罗马天主教和欧洲的伪造和虚构基础的一切。现在,在这种背景下,我想从修正主义的角度回答的问题是:在这些伪作存在之前,盎格鲁-撒克逊人和爱尔兰人是如何在黑暗时代皈依天主教的? 如果这一切都是由15世纪的意大利企业家凭空捏造出来的话,为什么基督教会以天主教的形式出现在帝国的边缘?

我认为更有可能的是,我们通常学到的历史更接近事实,即阿拉里克洗劫了罗马,从而开始了欧洲大陆的黑暗时代,欧洲和教会花了几百年的时间才从中恢复过来。然而,即使这不是真的,问题仍然是:

“为什么早在这些伪造品出现之前,英格兰和爱尔兰人就皈依了天主教?”

原创翻译:龙腾网 http://www.ltaaa.cn 转载请注明出处

Interesting article. A ravening hit piece, but interesting. The problem with most Orthodox (and the author is at least sympathetic to Orthodoxy, if not at least nominally Orthodox himself) historiography, apologetics and polemics is how biased against and unfair toward anything “Western ” they tend to be. This piece is no exception. It takes many good and important points about the fraudulence surrounding and novelty of the Gregorian Reform, then undermines it case by throwing in a kitchen sink of distortion and obvious falsehoods.

Just a few of these errors: Peter was not the head of the Church in Jerusalem, the proof of this is how while Peter was present at the Council at Jerusalem described in Acts 15, he did not preside. James “the Brother of Jesus” did. Peter is held by tradition to have been head of the Church in Antioch, attested to by the tradition of the Antiochian Church both Catholic and Orthodox, the existence of the ancient 1st century church there dedicated to him, and the wide witness of the Fathers.

有趣的文章。这是一篇令人垂涎的热门文章,很有趣。大多数东正教徒(作者至少是同情东正教徒的,如果不是名义上的东正教徒的话)的史学、护教和辩论的问题是,他们对任何“西方”事物都有偏见和不公平。这篇文章也不例外。它从格里高利改革的欺诈性和新新性中吸取了许多好的重要观点,然后通过大量扭曲和明显的谎言来破坏它。

这里有几个错误:彼得不是耶路撒冷教会的领袖,证据是使徒行传15章中描述的彼得出席耶路撒冷会议时,他并没有主持会议。“耶稣的兄弟”雅各才是。根据传统,彼得被认为是安提阿教会的领袖,安提阿教会的天主教和东正教的传统证明了这一点,那里有一座古老的1世纪教堂,专门为他而建,神父们也广泛见证了这一点。

Also, “Western” or “Latin” bishops did attend most of the Seven Ecumenical councils. The bishop of Rome is attested to have sent legates to them, who were accorded some precedence due to Rome’s recognized primacy. The Arian council at Rimini was held to northern Italy, and one can assume that many of the bishops in attendance were “Western” or “Latin” in so far as that anachronistic distinction (most of them probably spoke Greek, anyway) had any force at the time.

I personally think the revisionism attempted here is interesting and important. You undermine its force, however, by being too stridently critical (no Christian should reject any part of canonical scxture as fraudulent, for example) and obviously polemical. This strikes me as more propaganda than nuanced, dispassionate scholarship.

他也证明了父亲(德尔图良,伊格内修斯等)已经去了罗马,并在那里殉难。彼得在《彼得前书》第5章中写道“从巴比伦来”,这在圣经中——包括《启示录》——被认为是罗马的代号。

此外,“西方”或“拉丁”主教确实参加了七次大公会议的大多数。罗马的主教被证明曾派遣使节到他们那里,由于罗马的公认的首要地位,他们被赋予了一些优先权。

在里米尼举行的阿里乌斯会议是在意大利北部举行的,人们可以假设,许多出席会议的主教都是“西方人”或“拉丁人”……。我个人认为这里的修正主义很有趣,也很重要。然而,你通过过于尖锐的批评(例如,没有一个基督徒应该拒绝圣经的任何部分,认为它是欺骗性的)和明显的争论,削弱了它的力量。在我看来,这篇文章更像是宣传,而不是细致入微、冷静的学术研究。

A case can be made that Hagia Sophia was Christianized during the reign of the iconoclast basileus Leo III the Isaurian (717-741), when it was stripped of all its icons and sculptural work, or in 842, when it was redecorated.

Can anybody point me to sources (books, articles, papers) that discuss the pagan past of the Hagia Sophia in more detail?

“有一种说法是,圣索菲亚大教堂是在伊索里亚人巴塞勒斯·利奥三世(717-741)统治时期被基督教化的,当时它被剥夺了所有的圣像和雕塑作品,或者是在842年被重新装饰。”

谁能给我指出更详细地讨论圣索菲亚大教堂异教徒历史的资料来源(书籍、文章、论文)?

原创翻译:龙腾网 http://www.ltaaa.cn 转载请注明出处

First, the fact that these articles are being published anonymously is suspicious. The overall ideological slant of the writing seems to be what you would expect from a former KGB officer in Moscow. The idea seems to be to undermine the legitimacy of the Catholic Church by delving into every imaginable conspiracy and twist of the historical record to confuse people. The KGB produced this kind of Anti-Catholic propaganda for decades

Russians did it!

“首先,这些文章是匿名发表的,这一事实令人怀疑。这篇文章的整体意识形态倾向似乎是你对莫斯科前克格勃官员的期望。……”

是俄罗斯人干的!

图:很高兴你回家了,俄罗斯人在走廊里拉屎了!

Russian trolls everywhere!Run for your life! Save your soul (and do not think about what you have just read in the article or examine the sources on which the reasoning behind this article was built upon).

If there is a doubt about the validity of the narrative that you’ve been fed since very young, just blame on some pesky Russkie and poof it’s gone!

How convenient (how American…)

到处都是喷俄罗斯的!

快逃命啊!拯救你的灵魂(不要去想你刚刚在文章中读到的东西,也不要去检查这篇文章背后的推理所依据的来源)。

如果你对从小就被灌输的故事的真实性有疑问,那就怪到某个讨厌的俄罗斯人身上,然后它就消失了!多方便(多么美国化……)

Peace and joy. I thought that I had spent 20 years reading history. Now you explain to me that these were CAREFULLY crafted LIES. Clearly I’m gonna need another 20 years to re-educate myself. Churchmen are CLEARLY the biggest liars we have ever known. The fact that they pushed a FAKE religion at the expense of the ENTIRE history of Europe is beyond evil.

多可笑。

我以为我花了20年读历史。现在你给我说这些都是精心编造的谎言。显然我还需要20年的时间来重新教育自己。牧师显然是我们所知道的最大的骗子。他们以牺牲整个欧洲历史为代价来推动一个假宗教的事实,这是邪恶的。

“The fact that they pushed a FAKE religion at the expense of the ENTIRE history of Europe is beyond evil.”

The Devil had placed all sorts of false claims everywhere that led the people straight to hell, so the true history needed to be published instead. The moral stand was that the flock were saved to the true faith, and went to heaven, not that what was history faked by previous generations old pagans and Devil worshipers were preserved.

魔鬼到处散布各种虚假的说法,把人们直接引向地狱,所以真实的历史需要广而告之。寓意就是:羊群得救了,得到了真正的信仰,上了天堂,而不是前几代人伪造的历史被保留了下来,他们是老异教徒和魔鬼崇拜者。

You are, without a doubt, nutso. Have a nice day.

你真的是疯子。祝你今天愉快。